What is this phenomenon known as double counting? Why is it important? If you are shepherding clients through the OVDP program (or through streamlined domestic), or you are going through the program yourself, it is critical that you understand what it means and the governing principles behind it. Otherwise, you could be paying an offshore penalty that is substantially higher than what it ought to be.

Accounting for “double counting” is not child’s play. This blog will explain the principles behind double counting and what type of supporting evidence the taxpayer must produce in order to prove double counting to the satisfaction of the IRS. In what might raise a few eyebrows, the taxpayer carries the burden of establishing double counting.

As a refresher, the offshore penalty is determined by isolating the highest aggregate maximum balance during the disclosure period, which typically consists of the last eight years for which the tax return due date has passed. That balance becomes the base to which the 27.5% penalty applies (or 50% in certain cases).

Question number 37 of the OVDP Q & A asks, “If a taxpayer transfer[s] funds from one unreported account foreign financial account to another during the voluntary disclosure period, will he have to pay the offshore penalty on both accounts?” The answer is “no,” any duplication will be removed before calculating the offshore penalty. To reduce this concept to its bare bones, double counting may be taken into consideration in determining each year’s maximum aggregate balance.

This issue becomes relevant in the following situation: During the disclosure period, suppose Tom Taxpayer closes a foreign account at Bank ABC and transfers the remaining balance to a new or preexisting account at another foreign bank, which we’ll call Bank XYZ (note that the account need not be closed for double counting to apply … this is merely the facts of the hypo).

Must the highest balance in account ABC be taken into consideration for purposes of determining the aggregate maximum balance of all of John’s unreported foreign accounts during the year in question (i.e. the year that Account ABC was closed)? In other words, must assets in an account that was closed and transferred to another account be double-counted — once in the old account and then again in the new account?

The answer is “no.” However, it is not as simple as it might appear. The money transferred into the new account must actually have contributed to the highest balance in the new account before any duplication can be removed.

At first blush, one might assume that Tom need only establish that the closing balance was transferred from account ABC to account XYZ in order to satisfy this burden. After all, doesn’t that show that it wasn’t withdrawn and spent? Yes, but that thinking ignores the realities of banking today.

Keep in mind that if Tom’s XYZ account is anything like a traditional run-of-the-mill checking account, then it should come as no surprise that there is a significant amount of account activity during the year. By account activity, I am referring to deposits and withdrawals. From paying bills to buying groceries to entertaining family and friends, there is no question that Tom’s account balance rose and fell like the waves in an ocean.

This gets to the very heart of the problem. Suppose that the closing balance transferred over to Account XYZ from Account ABC was $ 50,000 (USD). Suppose that the date of transfer occurs at some point in time before Account XYZ hits its peak, or highest maximum balance. Suppose that between the date of transfer from Account ABC and the date Account XYZ hits its peak, numerous withdrawals are made that dramatically reduce Account XYZ’s overall balance (including the $ 50,000). Suppose that these withdrawals are followed by a significant infusion of cash. Has that $ 50,000 actually contributed to the highest maximum balance in account XYZ?

The answer to this question requires the tax preparer to play the role of a bloodhound and follow the trail, or “scent” of the money. As tedious as this might be, it is a good practice for the tax practitioner to engage in an “archaeological dig” to confirm that to the extent there were deposits and withdrawals following the transfer, that the withdrawals offset the deposits such that the $ 50,000 transfer was unaffected by any subsequent activity in Account XYZ. Only then can the taxpayer legitimately represent that the $ 50,000 actually contributed to the highest balance in Account XYZ.

If so, the $ 50,000 need only be counted once — as part of the highest balance in Account XYZ — and not twice. This will help rebut any challenges raised later that the $ 50,000 did not actually contribute to account XYZ’s highest balance for the year in question and thus, was inappropriately removed from that year’s maximum aggregate balance.

Here is a quick and dirty hypo to drive this concept home. John is a U.S. citizen with undisclosed foreign bank accounts. He has applied to OVDP. His disclosure period is 2006 to 2013. He has identified tax year 2012 as the year that contains this highest maximum aggregate balance.

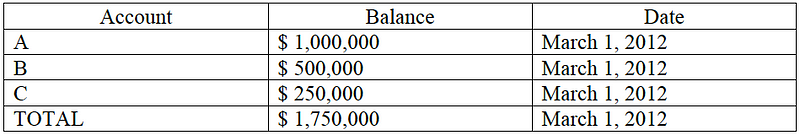

In 2012, John had three unreported foreign accounts at three different banks: Bank A, Bank B, and Bank C. Excluding interest, the total value of the principal (i.e., cash) in all three accounts was $1,750,000. As of March 1, 2012, the balances in the accounts were $ 1,000,000 (USD), $ 500,000 (USD), and $ 250,000 (USD), respectively.

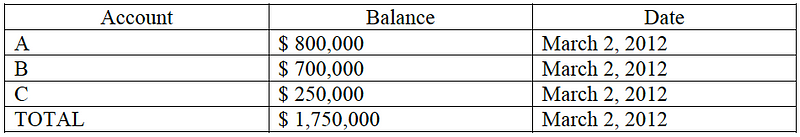

On March 2, 2012, John transferred $ 200,000 (USD) from Account A to Account B. As a result, his balance in Account A decreased from $ 1,000,000 to $ 800,000 and his balance in Account B rose from $ 500,000 to $ 700,000.

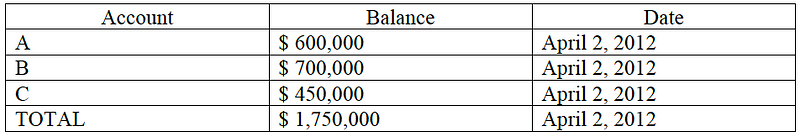

On April 2, 2012, John made a second transfer. He transferred $ 200,000 (USD) from Account A to Account C. As a result, his balance in Account A decreased from $ 800,000 to $ 600,000 and his balance in Account C rose from $ 250,000 to $ 450,000. The balance in Account B remained the same.

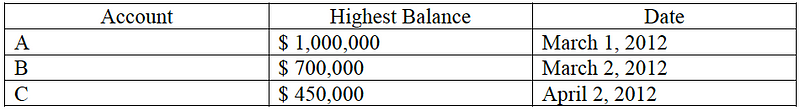

The first issue is to determine the highest balance in each account for tax year 2012. These are the amounts that John must report on his FBAR. For Account A, the highest balance was $ 1,000,000, reached on March 1, 2012. For Account B, the highest balance was $ 700,000, reached on March 2, 2012. And for Account C, the highest balance was $ 450,000, reached on April 2, 2012.

At first blush, it would appear as though the maximum aggregate balance of all three foreign accounts in 2012 is $ 2,150,000 (USD) (i.e., $ 1M + $ 700,000 + $ 450,000). Or is it? A simple comparison of the maximum aggregate balance of all three accounts and the total value of cash in all three accounts reveals a huge discrepancy. For example, the maximum aggregate balance of all three accounts is $ 2,150,000, whereas the total value of the assets in all three accounts is $ 1,750,000, a difference of $ 400,000.

Is there a “double counting” issue? Yes. Let’s break this down into smaller parts and examine each part separately. As a reminder, 2012 is the year during the OVDP disclosure period that contains the highest maximum aggregate balance. Therefore, we can disregard all of the other years and focus exclusively on 2012.

The critical issue is whether John must use the “inflated” maximum aggregate balance of $ 2,150,000 as the base to which the 27.5% offshore penalty applies. Or, may he account for “double counting” in determining his maximum aggregate balance? The answer to this question means the difference of more than one hundred thousand dollars in John’s miscellaneous offshore penalty.

If “double counting” is prohibited, then John’s miscellaneous offshore penalty is $ 591,250 (i.e., 27.5% of $ 2,150,000). But if “double counting” is permitted, then John’s miscellaneous offshore penalty is $ 481,250 (i.e., 27.5% of $ 1,750,000), a difference of $ 110,000. This is a stark difference.

Before John can pop the cork on the bottle of champagne and begin celebrating, he must take heed of something that might appear subtle, but that nonetheless has far-reaching results. Question number 37 explicitly states that the burden of establishing duplication — i.e., that funds were transferred from one account to another — lies on the taxpayer. Before John can adjust his maximum aggregate balance from the “inflated” $ 2,150,000 watermark to the “adjusted” $ 1,750,000 watermark he must provide adequate documentation to substantiate both transfers: (1) the $ 200,000 transfer from Account A to Account B and (2) the $ 200,000 transfer from Account A to Account C.

How might John do that? To borrow a famous line from the movie, All the President’s Men: “[By] following the money.” Let’s use the “Account A-Account B” transfer as an example. Recall that the “Account A-Account B” transfer occurred on March 2, 2012 and that it was in the amount of $ 200,000.

Examining agents recommend producing the following documents. First, a copy of the March 2012 “Bank A” statement showing a $ 200,000 withdrawal from Account A on March 2, 2012. Assuming that it was an electronic transfer, the Bank A statement might even identify the routing number of the bank to which this money was sent, along with the account number of the account.

Second, a copy of the March 2012 “Bank B” statement showing a $ 200,000 deposit. While it is unlikely that the $ 200,000 will be credited to Account B on the very same day that it was withdrawn from Account A (i.e., March 2, 2012), the fact remains that the Account B statement should still reflect a deposit date that is close in time to the withdrawal of funds from Account A.

After isolating the transactions on both bank statements, John should highlight them for the examiner so that they stand out among the sea of all other transactions. This way the examiner will not have to go on a “fishing expedition” to identity the relevant transactions. This will make it more likely that the examiner will accept the taxpayer’s claim of “double counting” without demanding additional supporting documentation.

But what if there are no account statements? Or what if the account statements are woefully inadequate? In that case, receipts can be used to validate the transactions. By receipts, I’m referring to a withdrawal slip from Bank A showing a withdrawal in the amount of $ 200,000 and a deposit slip from Bank B showing a deposit in that same amount. As in the case of the account statements, the dates reflected by these receipts must be close in time. Of course, it goes without saying that the $ 200,000 withdrawal from Account A must have occurred before the deposit of $ 200,000 to Account B.

Will John be able to meet his burden of establishing duplication? Assuming that he possesses one of the two types of required documentation, then the answer is, “yes.” In that case, his maximum aggregate balance will be $ 1,750,000, resulting in an offshore penalty of $ 481,250 (27.5% of $ 1,750,000).

Your tax attorney will need the following information in order to complete his or her review of your double counting issue. These steps must be repeated for every year in which you believe that there is a double counting issue. For each transfer, be sure to provide the following:

(a) The highest balance of the account from which the transfer(s) was made for the tax year in question;

(b) The highest balance of the account into which the transfer(s) was made for the tax year in question;

(c) The exact amount of the transfer in foreign currency along with a reference to the account statement that verifies this particular transfer;

(d) The account number from which the transfer was made;

(e) The account into which the transfer was made (i.e., its “final resting place”);

(f) The date of the transfer;

(g) The balance in the account (from which the money was transferred) immediately before the transfer was made along with a reference to the account statement that verifies this transfer;

(h) The balance in the account (into which the money was transferred) after the transfer was complete along with a reference to the account statement that verifies this transfer;

(i) A list of any and all accounts that were closed during the tax year, with special emphasis on whether the accounts from which the transfer was made or the accounts into which the transfers were sent were closed at any point during the calendar year;

(j) Assuming any such accounts were closed, identify the account and provide the date on which the account was closed along with the closing balance.

(k) The date on which the highest balance in the “receiving account” was reached.

(l) Focusing on a few random periods between the date of a specific transfer and the date on which the account to which the transfer was made hit its peak, prepare an itemized list of deposits and withdrawals. This will shed light on the issue of whether the withdrawals offset the deposits, such that the amount transferred was unaffected by any subsequent activity in the new account. This, in turn, will verify or discredit the claim that an amount transferred over actually contributed to the new account’s highest balance for the year in question.

For additional information on double counting, please see my blog post located here, https://www.deblislaw.com/ovdp-double-counting-traps-for-the-unwary/