How It Can Produce Surprisingly Gratifying Results For Foreign Persons

The simple rule for the source of interest paid by individuals has become an international tax shelter for tax-averse foreign persons. The active ingredient in virtually all international tax haven operations is the deduction of interest from a stream of business income otherwise subject to high taxation. The second ingredient is the deflection of interest, free of further U.S. tax, to some benign low-tax environment.

In order to understand how the source rule for interest can produce surprisingly gratifying results for foreign persons, it is necessary to understand the rule itself. And what is that rule? Interest paid by individuals, partnerships, and trusts takes its source from their place of residence. A natural corollary to this rule is that interest paid by individuals who are not residents of the United States has foreign source, no matter how intense their economic activity is in the United States.

The source rule for interest paid by individuals is a win-fall for foreign persons because it can be used to shield U.S. business income from taxation. How? By reducing U.S. taxable income by interest deductions on what is essentially self-owed debt. An example will help illustrate this point.

Suppose that Mark is a citizen and resident of Fredonia. He wants to purchase USAco, a U.S. business, for $ 1 million. USAco produces $ 150,000 of income per year. If Mark simply buys USAco directly with his own money, the annual income of $ 150,000 will attract U.S. income tax of roughly $ 60,000 at the current rate of 40%.

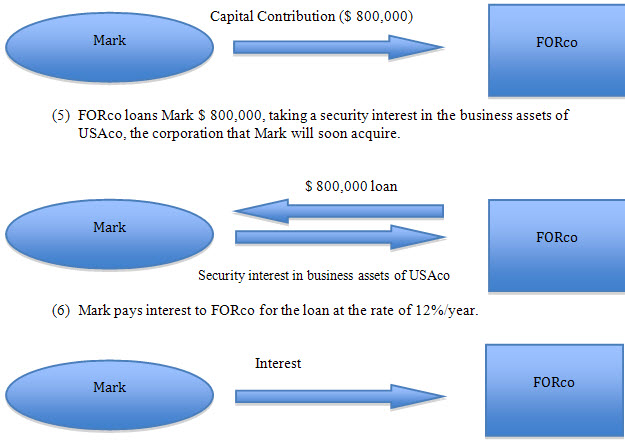

Instead, Mark borrows $ 800,000 of the purchase price at 12% interest from FORco, a foreign corporation in which he owns all the stock. Prior to the transaction, Mark transfers the funds to FORco as a capital contribution. He then secures the loan from FORco with the business assets of the U.S. corporation that he will soon acquire. Below is an outline of the transaction along with schematic diagrams:

(1) Mark is a citizen of Fredonia, a foreign country.

(2) Mark wants to purchase USAco, a U.S. business.

(3) Mark forms FORco, a foreign corporation. Mark owns all of the stock.

(4) Mark transfers $ 800,000 to FORco as a capital contribution.

To simplify matters, it may be helpful to analyze this transaction from two different points of view: Mark’s and FORco’s. Let’s begin with FORco. What are the tax consequences to FORco for the interest payments it receives from Mark? In order to answer this question, it is necessary to refer to the source rule for interest.

Is the interest paid foreign source or U.S.-source? As a preliminary matter, why does that even matter? If the interest is foreign source, then it is not exposed to U.S. taxation in the hands of FORco. But if it is U.S.-source, then it is subject to U.S. taxation in the hands of FORco. Here, the income is foreign source. Why? Because interest paid by an individual takes its source from his or her place of residence and Mark is a citizen of Fredonia, not the United States. Therefore, the interest is not exposed to U.S. taxation in the hands of its recipient, Mark’s wholly-owned foreign corporation.

The one caveat to that is if FORco owned a U.S. business and the interest it received derived from the activities of a U.S. office operated by that business. In that case, the foreign-source interest would be subject to U.S. taxation. This hypothetical is far-removed from that scenario. Unlike Mark, FORco is not engaged in a U.S. business. While FORco has a security interest in property belonging to a U.S. company, merely holding debt secured by property in the United States does not of itself constitute a U.S. business.

Let’s turn to Mark. Are the interest payments that Mark made to FORco deductible from the income that he derived from USAco? Yes. How does that affect USAco’s taxable income? First, let’s look at how much Mark’s interest deductions amount to each year. They amount to $ 96,000 (12% of $ 800,000).

With annual interest deductions of $ 96,000, Mark’s taxable income from USAco is reduced from $ 150,000 to $ 54,000 ($ 150,000 (-) $ 96,000). And Mark’s U.S. income tax is reduced from roughly $ 60,000 ($ 150,000 x 40%) to roughly $ 21,600 ($ 54,000 x 40%). This is an extraordinary result for an exercise that required no more than a day or two of paperwork.

But why stop there? It may seem that Mark could eliminate all U.S. taxable income by borrowing the full purchase price of $ 1 million at 15% interest from FORco. This, however, would be costly mistake. First, the rate of interest charged on loans between related persons is subject to revision by the IRS if it departs from an arm’s length transaction. And second, the allowable interest deduction in such scenarios is limited to interest on debt not exceeding 80% of the assets of the U.S. business paying the interest.

It is hard to imagine that this simple source rule has such far-reaching consequences. But it does. Indeed, it strips taxable income away from the U.S. Treasury not once but twice. And how does it accomplish that? By interest deductions.

This strategy can be reduced to two steps. First, interest paid by Mark to FORco for the $ 800,000 loan is deducted from income generated by USAco. That step results in a substantial reduction of USAco’s taxable income in the United States. Second, those same interest payments are excluded from U.S. taxation in the hands of its immediate recipient, FORco, a company related to Mark.

These steps reveal an inconvenient truth: that the simple rule for the source of interest has become an international tax shelter for Mark. Indeed, at the very core of this strategy lies the essential element of all international tax-haven operations: the deflection of part of an income stream (by deductions from income that would otherwise be heavily taxed) to an environment where it is less heavily taxed, all the while remaining under the same beneficial ownership. To steal a phrase from Shakespeare’s timeless classic, “Romeo and Juliet,” “a rose by any other name would smell as sweet.” In effect, this transaction is nothing more than a self-loan from Mark to his wholly-owned finance company.

The question thus becomes, “Can this structure withstand an attack by the IRS?” You can see it coming. The IRS is marching forward. You can hear their drums beating and their guns being fired off in the distance. What will they argue? You guessed it. The IRS will challenge the reality and business purpose of FORco, the foreign corporation interposed by Mark to channel funds to his own U.S. venture.

For those of you who are cynical that this structure will survive such an attack, you may be surprised to find out how resilient it actually is against attack. What makes it so resilient? A fundamental principle of the U.S. tax system: that a corporation has its own identity, separate and apart from its owners. Here, FORco is neither transitory nor a pure conduit. It has permanent assets and owns and retains the interest it receives from Mark.

That’s not to say that this structure cannot be strengthened further against IRS attack. Indeed, it most certainly can. In what way? By expanding the range of economic activity of FORco. For example, if FORco engaged in business or invested elsewhere in the world, financed other projects of Mark’s, lent to investors other than Mark, borrowed from other sources, and above all had other owners besides Mark, it would be untouchable. But even as it stands, Mark’s structure is solid.

Before you jump up and down or scream for joy (I’m sure that you are sitting on the edge of your chair and that you can barely contain yourself), it is important to understand that this strategy is limited in practice. Indeed, it only works for U.S. businesses that are directly owned by foreign individuals. In other words, if Mark had acquired USAco through a corporation – U.S.-chartered or foreign – that would be fatal to the tax shelter. Why? Because the payer of interest would no longer be a person but instead a corporation and interest paid by a domestic or foreign corporation has U.S.-source if attributable to the operations of a U.S. business. Needless to say, interest is always attributable to the operations of a U.S. business if the underlying loan that the acquiring corporation received was used to purchase a U.S. business.

What does this mean for Mark? Mark must make a choice between tax benefits that can only come through direct ownership of USAco and the advantages of the corporate form. If he chooses the tax benefits, then he must sacrifice the advantages of the corporate form, consisting of limited liability, anonymity, and insulation from U.S. transfer tax.

A natural consequence of this limitation is simple, but often overlooked. Mark’s plan is limited in practice to small and medium-sized businesses that lend themselves to individual or family ownership. Indeed, the plan cannot be used for an automobile assembly line or a petrochemical plant. The opportunities for earnings-stripping through elaborate offshore structures built on tax treaties and tax havens have become so sharply constrained in recent years that tax-averse foreign persons may begin to give Mark’s simple plan a hard look.

So far, we’ve only explored the U.S. tax consequences of this strategy. In order for Mark’s tax shelter to work, both the U.S. and Fredonian systems must permit it. What the U.S. offers is the particular source rule that allows escape of some business profits from the U.S. tax environment as deductible interest.

If Fredonia (Mark’s country of residence) imposes low or no income tax, U.S. tax is the only concern. The source rule by itself is all that is needed to defeat the wrath of U.S. taxation. But if Fredonia is a high-tax country, that presents more of a challenge. In that case, Mark may have dodged a bullet just to face a firing squad.

The entire plan will fail unless Mark can keep FORco’s income beyond the reach of Fredonian taxation. Of course, that’s not something that Mark can control unless he would like to spend several years at “Hotel Fredonia,” where he can check-out any time he likes but he can never leave. The only way to salvage the plan is for Fredonia to respect the separate, untaxed status of FORco and not subject its income to taxation in Mark’s hands. In other words, when Fredonia is a high-tax environment, the structure works only if Fredonia does not reach or look through foreign entities owned by Fredonian persons.

This raises another problem in international tax haven operations: the extent to which national income tax systems look through separately chartered entities owned by persons subject to their taxation. If Fredonia were to respect the formal separate identity of FORco, the resulting tax regime would be one of deferral. And that is better left for another day.